Pulte Institute Evidence and Learning Associate Director Danice Brown Guzmán and her colleague at Notre Dame’s BIG Lab, Teaching Professor Eva Dziadula, are the authors of a recent article in the International Journal of Development and Conflict exploring the interplay between child labor — those ages 5 to 13 who work at least one hour a week — and school attendance in Nepal, revealing stark disparities influenced by work type and the reporting source.

Guzmán and Dziadula's findings are particularly relevant as child labor is increasing worldwide after decades of decline. The impacts of COVID-19 have put millions more children at risk, underscoring the urgent need for gender-sensitive interventions and policies to address the challenges faced by working children. Their research offers new insights into child labor statistics and their implications for global education policies.

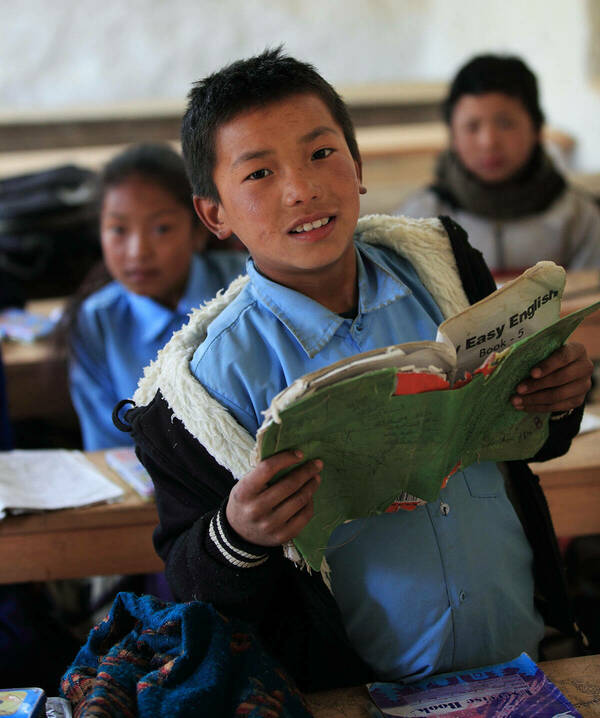

An 11-year-old boy reads a textbook in a Bhaktapur, Nepal classroom. Credit: Werli Francois / Alamy

In Nepal, children working in markets miss nearly 1.5 more school days weekly than their non-working counterparts. This figure escalates for girls involved in domestic chores by an additional 0.4 days per week, as reported by the children themselves. (Conversely, data from adult household members suggest a less pronounced connection between child labor and school absenteeism.)

Through a randomized survey experiment, Guzmán and Dziadula evaluated adults' perceptions of the benefits of education, uncovering a generally lukewarm attitude. This lack of enthusiasm suggests a likely underestimation of school absenteeism, particularly among girls. Despite the illegality of child labor for those under 14 in Nepal, it remains pervasive. Guzmán and Dziadula discovered that many working children spend over 10 hours per week on the job, with older children from smaller and female-headed households bearing a heavier workload.

The study also revealed a significant gender disparity in student and labor engagement. More boys attended school without working compared to girls, while a larger portion of girls were engaged in domestic tasks alongside their schooling. The reasons for school absenteeism varied by gender, with boys being more likely to skip school due to disinterest and girls due to family obligations.

In interviews, dozens of adult male respondents noted a significant decline in school attendance among boys involved in labor. This indicates that men are more attuned to how boys spend their time, leading to more precise reporting. It also underscores the role of men as primary earners: coupled with opportunities for boys to find manual labor, this can create pressure to skip school. Still, boys generally achieve better educational outcomes than girls.

What’s Next

Guzmán and Dziadula say that more robust research is needed to understand the factors behind varying perceptions and to assess the impact of public investment and compulsory schooling in reducing child labor, using successful interventions in Turkey as a reference point.

They also advocate for more reliable data collection methods, such as using administrative attendance records, emphasizing the need to equally promote the benefits of education for both boys and girls. This highlights the significant challenges in Nepal's educational environment that impact all children.

Guzmán and Dziadula underline the importance of tailored interventions that address the specific conditions of working children in low- and middle-income countries. They suggest that further studies to examine the nuanced impacts of different types of child labor and the educational disadvantages these children face. For instance, their analysis shows that children working in markets are at a higher risk of educational neglect than those engaged in domestic tasks.

Guzmán said education is widely recognized for equipping children with essential knowledge and skills, improving their future job prospects. She added that enhancing access to quality education, providing scholarships and financial aid to families, and bolstering legal frameworks and their enforcement “can create a future where children can fully realize their potential through education instead of being confined to labor.”

“Target 8.7 of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals aims to eradicate all forms of child labor by 2025,” Guzmán said. “Our research indicates that significantly increased efforts are urgently necessary to achieve this goal.”

Read the article in the International Journal of Development and Conflict

Authors' note:

This paper utilizes data collected at the baseline of a randomized controlled trial funded by the U.S. Department of Labor to study the impact of UNICEF's child labor intervention in Nepal. The evaluation was led by Lila Kumar Khatiwada and former Pulte Institute team members Juan Carlos Guzmán and Tushi Baul. Nepal’s National Labor Academy collected the data. Research Assistant Hannah Reynolds supported the literature review.

Full citation:

Dziadula, Eva and Danice Guzmán. "Do Working Children in Nepal Miss More School? Depends Who You Ask.” International Journal of Development and Conflict 13(2023): 159–193